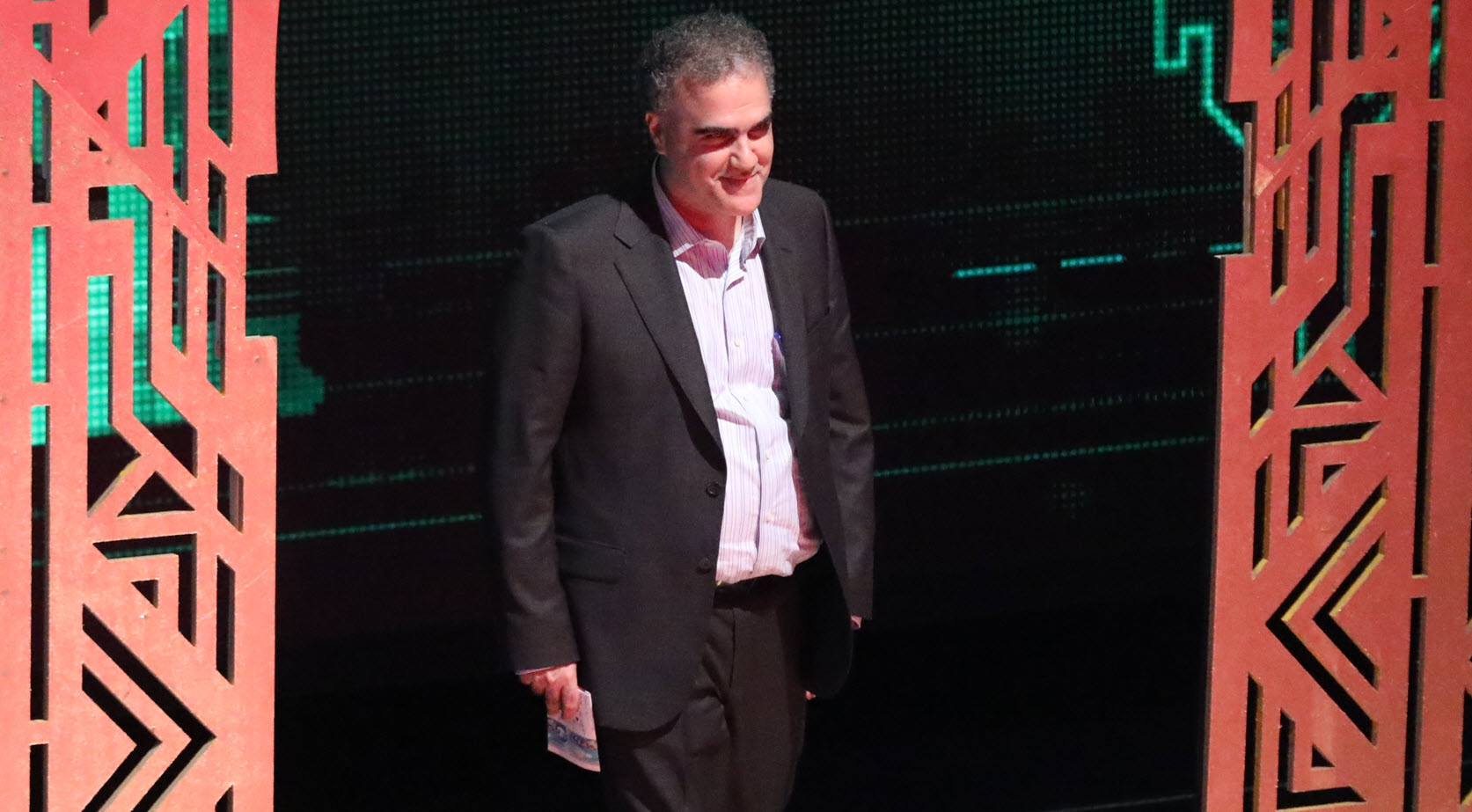

A puzzling illustration in a school biology book first drew Hossein Baharvand toward embryology. Today, the 2019 Mustafa(pbuh) Prize laureate is one of the most prominent figures in stem cell research in Iran.

MSTF Media reports:

Hossein Baharvand, a Mustafa(pbuh) Prize laureate from Islamic Countries, talked of developing curiosity for biology, how he got to work on Stem Cells at the Royan Institute, and his latest efforts to develop silence, particularly regarding children and underprivileged regions.

A known figure in Stem Cell research in his home country, Iran, and all around the world, Hossein Baharvand is a biologist at the Royan Institute. In the 70s, Baharvand, along with a few up-and-coming researchers, took the first strides in stem cell-related research.

He focused his efforts on the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), for which he was honored at the 3rd edition of the Mustafa(pbuh) Prize in 2019. Ever since, he has kept conducting further groundbreaking research on these two areas at Royan. He has also founded several research centers across cities in Iran.

In an interview, Baharvand told us about his career and research over the decades, especially at Royan, and why he is going to study pluripotent stem cells. In the following, read the first part of our interview with the Mustafa(pbuh) Prize laureate:

Can you talk about the turning points in your academic career and how it all started?

Baharvand: I chose to study math in high school because I wanted to enhance my cognitive function and study medicine at university. It was in my last year of high school when I came upon an experiment in my biology textbook. I didn’t comprehend it but I found it fascinating.

When I enquired of my biology teacher, he told me that “the science is called Embryology.” If I wanted to study that field, according to him, I had to study pure biology, enter the field of medicine, and then study embryology.

In summer 1989, some time after that conversation, I made up my mind to be an embryologist. I had become interested in a subject the nature of which was not exactly clear to me. It was only later that I realized that the incomprehensible experiment was the research that earned Hans Spemann his Nobel Prize.

I was so fascinated I couldn’t wait to find out about the embryonic development of human beings and animals. There is this saying that God will put the right people in your path. My mother always prayed that I meet the right people and so I did.

I studied pure chemistry at Shiraz University. When doing my BSc., I met amazing people. Dr. Rostami, who intended to establish an infertility treatment center, asked me to join his team. I happily accepted the offer but I had to refuse later because I had to move to Tehran to continue my studies.

I came in first in my graduate entrance exam and at last got to study my dream field, embryology, at Shahid Beheshti University. I tried to get a position at the Royan Institute and I finally did in 1995.

We worked round the clock. We did not even have enough tools or precise scales. We had to wait until we got off our shift. At around 9, we would head to the lab with our ingredients to develop cell culture. We often worked till 3 or 4 in the morning, weighed ingredients and mixed them to prepare the conditions for cell culture. We would head back to the lab again after three hours of sleep.

The late Dr. Saeed Kazemi, who was a PhD student at that time, worked with us at the lab. He was one of those “right people” whom God placed in my path. The question that occupied our minds at the time was whether we could fertilize mouse sperm and eggs in the lab to create a single-cell embryo and then grow it to a few days old.

The development process is such that, for example, a single-cell embryo divides into two cells, which will in turn divide into three and four cells, and so on. After that, these cells become very dense and resemble a strawberry, which is called a “morula” in Latin.

Next, the cells spread apart again, resembling a hollow ball containing 100 to 200 cells. If we look at this hollow ball in two dimensions, it looks like a ring with a gem. The ring creates the “pair” and the gem creates the “embryo” (us). Unlike regular rings, this gem is located inside the ring so that this part is not damaged when the embryo migrates through the fallopian tube to reach the uterus and implant.

We grew the embryo to the stage where it became a hollow ball called a blastocyst. The question was what to do with those. We decided to transfer these embryos into the uterus of a mouse to see if mouse embryos would be born.

This was unprecedented because implantation does not occur merely by transferring the embryo to the mouse uterus, and mechanisms must be activated in the mouse's body. We did our experiment and fortunately, a few months later, we saw the birth of the mice.

At the same time, we succeeded in fertilizing mouse sperm and eggs in the laboratory to the point where a high percentage of single-cell embryos reached the hollow blastocyst stage. I found the transfer to the womb very interesting but there was always the question, “What next?”

It was around 1998 or 1999 that an article was published in the scientific journal Science. The subject was the production of human embryonic stem cells from human blastocysts in a laboratory environment, from which scientists were able to create other types of cells. This was what I was looking for. I loved the ways of creation and was eager to know how nerve cells or heart cells are created in humans.

How did you move from stem cells to studying pluripotent stem cells?

Baharvand: Due to ethical and scientific reasons, I could not directly study the human heart and brain during the embryonic period, but I carefully studied the existing literature. A year or two after that paper, another one was published in the journal Nature Biotechnology by an Australian research group who had succeeded in doing this. The sum of these findings led me to focus more on this issue.

I found out that mouse stem cells were produced for the first time in 1981, and an article about it was published in Nature. Later, around 2010, the scientist who first invented the “in vitro fertilization” (IVF) method received the Nobel Prize.

After that, in 2012, another scientist who had succeeded in returning skin cells to the embryonic stage and reprogramming them for the first time received the Nobel Prize, thus opening a new door in science.

Around 2000, I became interested in seeing how we could go from stem cells to “embryonic pluripotent stem cells.” After we achieved this technology, we thought that perhaps these cells could also be used to treat diseases, and fortunately, a few years later, this became a reality. Therefore, our initial motivation was to discover the hows of creation, and we did not initially have a purely therapeutic goal in mind.

What do you think about the popularization or the promotion of science?

Baharvand: To achieve greater prosperity in the future, we must increase public awareness of science.

You have attended the Mustafa(pbuh) Prize Science Cafes, which were well-received by participants. Yoy have also presented a booklet by the Royan Research Institute at the Science Promotion Exhibition that explained stem cells in simple language for children and adolescents. What other efforts have you made in promoting science? Have you felt the need to do so?

Baharvand: Right from the beginning, I firmly believed in this matter, so we launched a laboratory called “Stem Cells for All.” We converted a bus we had rented from the then-Tehran Municipality into a mobile laboratory so we could demonstrate science directly to students at schools.

Unfortunately, this bus, which we had spent a lot of money on equipping, could not operate for a long time. Through donations, we can equip a more suitable bus and take science to schools and underprivileged areas.

Also, my colleagues and I are trying to hold one-day conferences at nearby universities so that we can share some scientific findings with others in simple language.

Using a bus as a mobile lab is an interesting idea, being implemented in many advanced countries today.

Baharvand: It is. We started it in 2009, but unfortunately it stopped after a while. I am hopeful that better opportunities will be provided. As teachers and researchers, we will do anything we can for our country, but those with executive responsibility who do not perform their duties properly must be held accountable.

In 2019, you received the Mustafa(pbuh) Prize for the treatment of Parkinson's and Eye AMD with stem cells. How did receiving this award change your life? Did the recognition gained from this award have a positive impact on your professional life and make your achievements more visible?

Baharvand: It feels wonderful for your efforts to be seen. More importantly, being seen gives you extra energy to complete the task.

Ever since winning the Mustafa(pbuh) Prize, we have taken many steps to further the research and obtain the necessary permits to perform transplantation in humans. Of course, it is the kindness and love of others that make our actions and efforts seem great in their eyes.

On the other hand, granting such awards can motivate students to believe that they too can one day achieve such achievements and be among the winners.

I believe what you seek seeks you. As Rumi has beautifully put it:

You are a treasure, if the gems are your aim.

No more than a grain, if a loaf is your claim!

Recall this secret, when you play this game:

Whatever you pursued is what you became.